Art for the End of Your Strength

Elaine Elledge's upcoming show uses fragile domestic and medical materials to explore chronic illness and early parenthood.

“I hope there will be a lot of people who see my work and say , ‘Oh. I know what it means to feel utterly at the end of my strength. I see myself in this.’”

You don’t need to be an artist or parent to savor the wisdom in the conversation I’m sharing with you today! You’ll find a dynamic exploration of dedication in the work that matters to us, listening to the materials of our lives to show us the truths about where we are, and the empathy that comes from accepting our own stories.

I used to do more interviews but they are, frankly, a lot of time to edit. So the practice fell off during my earliest years with Pippin. But I want to do more of it because I get such giddy butterflies thinking of you all experiencing Elaine in this space.

Elaine Elledge is a role model to me. We’ve known each other since undergrad at Penn State University and have had more than one conversation about art. I even curated an exhibit in a rotating space that included Elaine’s work in 2011! It’s been a privilege to get to follow her work this long and see it evolve and change with her. Her youngest is just a few months older than my Pippin. It’s a happy accident we’re in the same city after many years in different places.

I’ve wanted to talk to her for a long time for this newsletter and today is the day! She has an upcoming show at the art museum in Harrisburg that I cannot wait to experience.

I admire her work so much. I admire her as a parent and a fellow chronic illness pilgrim. I admire her dedication. We have an understanding between us of the life we are trying to live and work we are trying to make. There is very little that has to be explained or explicated beyond what is relieving to us both to discuss.

You have to read her artist statement for the show. It’s so beautiful. (Full transparency: I edited it)

Quick excerpt though before we jump into the conversation:

[ My art is made in] small segments at the end of nap time, after dark, after tea, after story time. I mean literal margins of time but also margins of strength. Between moves, babies, and autoimmune diseases, making art is not done out of abundance but exhaustion and weakness. It is necessary; it is beautiful; it is hard.

Despite the margins being small, my internal world feels quite large. My internal world is always bursting at the seams, begging to be let out. This piece was a chance to release my internal world. To let it flow out, as big and as loud as it longs for.

My words are in bold, italics. Elaine’s are in regular text.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about trying to make sense of “making in the margins”. You are exploring that idea in your upcoming show. How do you make sense of “margins”?

By "margins", I think I mean that I do almost everything in life on the last scrap of strength (or at least it feels that way), and have lived significantly outside my window of tolerance for large sections of time (something I've been working desperately to change). This is not an ideal way to create things, but honestly, I get so depressed if I don't make something, it's like fighting from ahead and behind.

I would say the show is about the one the weary wonder of motherhood. So the paradoxes of weakness, but also beauty. Finding beauty in impermanence and fragility.

It’s hard to be devoted to making art. And I have been devoted to it. And it's not always easy to be devoted to things.

And after the show is done, I need to take some time to focus on my health. I have several chronic illnesses that aren’t fully managed. I’ve been okay but also not okay? But what am I going to do? I'm going to the studio to work. It’s a really deep dedication.

The whole show feels really vulnerable to share, especially the commissioned window installation that will face 3rd Street where everyone can see it. It’s a large installation that is truly emotional and unhinged. This piece is unpolished and exactly-where-I'm-at.

It’s constructed of a large set of Kozo paper diamonds sewn together. They're eight feet by eight feet. And there are four of them. I sewed them all together and beneath them hang waxpaper strips. And then I altered them by dipping them in blueberry dye and water and crushing blueberries against them and laying them out on a big sheet and splashing watercolor over them. I sprayed them with some herbal iron supplements that I had from my pregnancies. I sewed along them, adding little pieces of papers gathered along the way.

I thought about remaking it. I have the skill to construct it in a clean and tidy way. But I talked with my husband Grant about it and he said, “No. Clean is not the point of your concept. Yes, this is raw and it’s what you're about.”

He was right. The way it is now is very real. I know what I've been through in the last few months and I can look at it and recognize my experience.

I know paper is really important to you. What other materials will we see you use in this show?

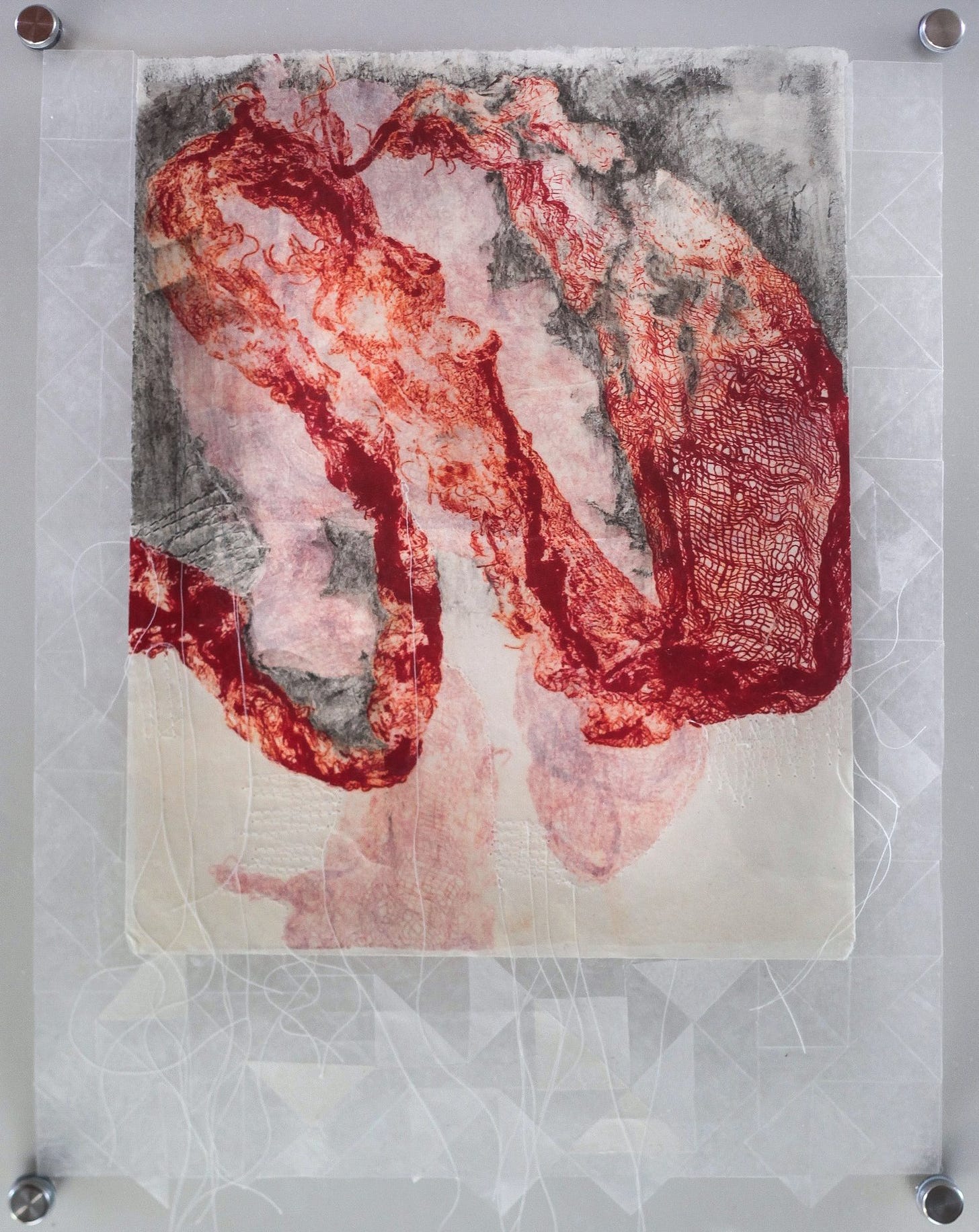

My training was originally print making and you can see that influence here. A lot of cheese-cloth impressions. Some cyanotypes. A lot of red ink. Fabric imitations and stitching. Clotheslines and pinning.

You’ll also see pieces of cloth that are stretched out or loose. Pieces of thread or dangling or suspended; the paper is cut, sewn, punctured. I hope every viewer sees it as beautiful or aesthetically pleasing but also that there is a lot of hardship or difficulty, wear and tear.

It’s all incorporating materials from the medical and the domestic.

Having seen your work over a decade now, there was a significant change at some point in the topics and representations you engaged with in your work. What prompted that change?

I was in a cohort through a nationwide network of artists and mothers when I was pregnant with my second baby. It was very formative to my work and process.1

Danila Rumold was my mentor through the program and afterwards till her death this year from breast cancer. She worked with Kozo paper which she describes as a 20 year love affair with the material. Her influence on these pieces is very clear .I loved watching how she manipulated the paper. She had projects where she put the paper into a washing machine and pulled it out–the paper is really thin but it holds up well to water!

I had already started to explore Kozo paper because it's a thin flat rice paper kind of thing that is less expensive than some of the cotton papers I had been using. And the material is a direct embodiment of everything I explore in my work. Here's a surprisingly strong and surprisingly thin type of paper! It has a tenacity which is surprising given how transparent and thin it is.

So basically, almost every piece in the show is made from Kozo paper. And if it's not Kozo paper, it's wax paper or parchment paper from my kitchen drawer.

I've been really interested in wax paper for a long time. It’s inexpensive. It comes in large rolls. It’s beautiful. It possessed me at a very low moment in my parenthood journey; one of the pieces in the show is from this period, six by six inch quilts of wax and tracing paper. My first son did not sleep and it was traumatic for me. I was awake nights on nights. One night, I just couldn’t stop thinking about wax paper. It just entered my mind and became an obsession literally overnight. So the next day I started cutting inch squares of wax paper and playing with them and studying them.

I love exploring material properties, how I can manipulate them and what their manipulations mean for my concepts.

I love the way the materials become a metaphor that you're using to make sense of and give visibility to an experience of parenting and illness. You’ve crafted a dialogue; the materials teach you and then you shape the materials. Which is also the process of parenting–you have this person that's not you that you're studying all day every day. And then they are changing you. And then you're changing them. Back and forth.

Yeah, that's true. You get a lot of ideas that you wouldn't have from talking to your materials. And your kids.

Another big piece of this was learning to use materials in small time increments. In the artist cohort I was in, we talked a lot about how to get the work done while being a primary care giver. It was wonderful to have people to share that with. The camaraderie was so meaningful.

Danila emphasized making things in small bits that you can add together or piece together into a larger work. What is something I can do in five minutes? And over a year, what can those 5 minutes add up to? These are the margins we have to work with and these are the margins represented in every piece of the show.

Before being a parent, I would make individual pieces in rectangle form. It was mostly wood block printing; I could carve a picture onto the wood. I still love that process and expect to do much more wood cutting in the future, but it requires that I sit down for longer periods of time. They're not pieced together, they don't add to anything larger I want to make. I want to make large, experiential embodied work.

I'm also really interested in depicting fabric or fibers through whatever meeting medium I pursue. Many of the pieces in the show are from taking cloth and printing it directly onto the paper. I can make a large quantity in a small amount of time which is a practical solution to the stage of life I’m in. And I also think it's really beautiful. I am really drawn to the thicknesses and the thickness and the flow, the way you can see the cloth, ebb and flow on the paper and the way the inks gather in certain areas and stretches out in certain areas and the way you can see the threads.

I worked on our third floor because it was the emptiest part of the house. And there was a spare bed in that room beside the crib, waiting for his arrival. And I was laying in bed because I was physically unable to do anything. I felt angry.

I had been working with a brown color throughout the cohort. Red had initially seemed too menstrual. I knew the brown was not communicating what I felt. I put the brown ink piece I had worked on over a whole year under my bed. It never saw the light of day.

From that moment on, I printed in red. I felt it much more accurately captured everything that I had been through. Sometimes you just don't know something until you know it.

When did you get the celiac diagnosis?

February 2022.

So you went through two pregnancies severely, malnourished.

Grant, my husband, and I laugh at how absurd it was to do that with an undiagnosed disease. And then I breastfed both of them. Breastfeeding is so complicated.

It's so complicated knowing what to do if you're a kid versus what to do for yourself. I look back and I don’t initially remember why I breastfed as long as I did. Then I remember there were circumstances that made that process complicated. Mine were Elsie’s food allergies, her inability to take a bottle, and my oversupply making weaning painful.

It is so hard to look back and understand our decisions. But I think that level of care is not lost either. The same way I don’t think my era of brown ink and abandoned pieces was a waste. Any care given is valuable.

And no two circumstances are the same so no two forms of care can be the same. Every chronic illness operates completely differently; there's no one way to manage a chronic illness. There's no one way to try to survive postpartum. There are so many nuances that are so contextual.

Acceptance is one of my highest values and I feel anytime someone asserts, “This is the best way to do this!” then I’m like tilts head in skepticism. Let’s hold some room here for a question!

What does acceptance mean to you?

Holding space for people is really important to me. When somebody says, “This is my experience” I believe them. The world is very gray to me, not black and white. I aspire to be someone who admits I don't know about a lot of things. Who am I to say, “No, it should be this way for you.” No! That's your view! You're beautiful. Let's be friends!

How does that mentality extend to your work and yourself as you're working? Do you see yourself having to practice acceptance of your own story in the process of making the art or is the art of the practice of coming to acceptance of your story?

I struggle with acceptance more with myself than I do other people, which is something I'm working on. I think that I have struggled with that a little bit with this show. Because I don't feel my circumstances are very exceptional. In one way, I can tell you the details of my experiences with celiac disease, mental illness, possible fibromyalgia and hand tremors and I’m with my kids full time… but that’s the story for so many people. Our world is rife with people struggling with mental illness and chronic pain and parenting.

I have to go back and reaffirm myself a little bit. My primary motivation is often to not make a fuss. But I also want to hold my experiences in a healthy way, to be able to say, “Elaine, what you went through was really difficult for you and that's okay. You don't need to run from that.”

What do you hope people leave with when they see your art?

The show makes a new era of my life—my youngest starts preschool this fall. So the collection is my retrospective of early parenting. When I stop and think about what it will be like to see these pieces in one space, I get emotional.

I tend to believe in my story and my art as much as it represents a shared human experience. I hope there will be a lot of people who see my work and say , “Oh. I know what it means to feel utterly at the end of my strength. I see myself in this.”

Experience More!

See Elaine’s work at her website.

Her show Margins and the Height of the Sun opens June 21, 2024 at the Susquehanna Art Museum in Harrisburg, PA.

Opening reception is 5-8pm.

At 6pm, Elaine will conduct live performance where she will sew the panels seen in the piece And Furthermore together. Visitors will have the opportunity to see her activate this performance-based sculpture in real time.

*The cohort Elaine was part of began as part of the Artist and Mothers podcast group and now operates independently as the Thrive Together Network.*